Looking back at the history of Playboy magazine, it’s clear that Hugh Hefner wanted the publication to play a role in the development of the modern gentleman. It did that through incredible interviews, but also by elevating new fiction writers and popularizing genres and subjects that didn’t have a huge number of other outlets. It’s clear today that Playboy deserves a huge amount of credit for taking science fiction writers seriously at a time no one else would look at it twice.

Playboy published tons of high quality fiction in its heyday from both big-name writers and relative newcomers. It’d be a tall order to make a comprehensive list or definitive ranking of all that is out there. But you can do worse than knowing these stories that 10 authors published in the pages of Playboy.

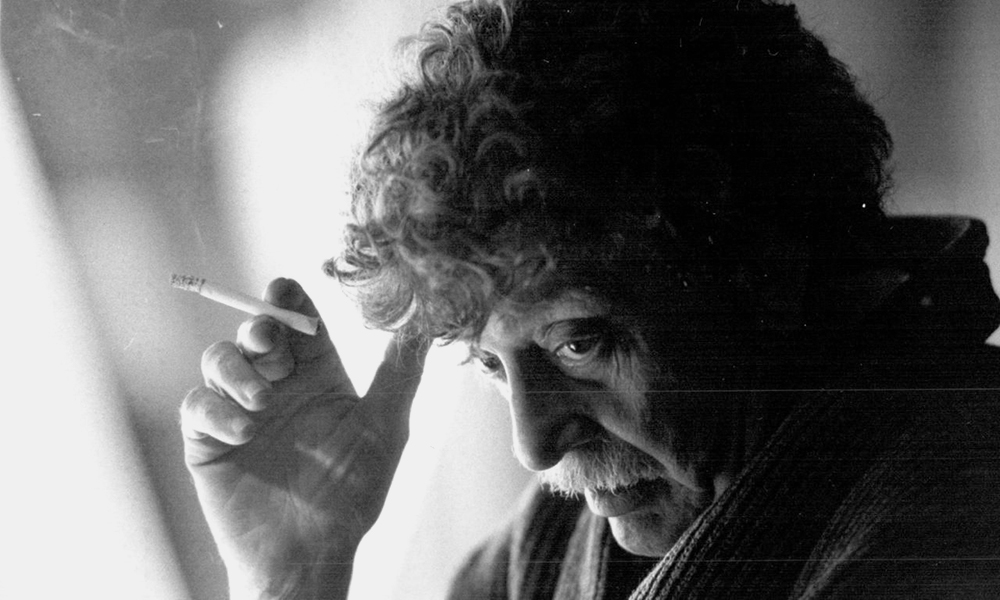

Ray Bradbury

Story to read: Fahrenheit 451, published in 1954

It’s weird knowing that a story many people had on their high school English required reading list was originally serialized in Playboy. But the story was important in building Playboy’s reputation in its early days. A year after it was published as a novel and got little attention, Fahrenheit 451 was serialized in Playboy in three parts in March, April, and May of 1954. It was a year after Playboy started, and it was still trying to prove its validity as a magazine that contained both nude women and thought provoking literature. It worked. Playboy had its reputation boosted and Fahrenheit 451 shot up in popularity and is relevant to this day.

Joyce Carol Oates

Story to read: Saul Bird Says: Relate! Communicate! Liberate!, published in 1970

Joyce Carol Oates is by no means the only female fiction writer published by Playboy, but she does stand out in how she defended herself and other women contributors. Oates was called out by the National Organization for Women for her involvement with the magazine. In her written response, Oates said the pictorial aspect of Playboy was of little interest to her, but she was unwilling to dismiss the magazine on that basis only. She talked about the other, non-pictorial pages being full of worthwhile material and the magazine itself being a surprisingly liberal publication with wide appeal and the ability to spark genuine conversation and growth.

It’s that kind of dismissal and obedience that her story, “Saul Bird Says: Relate! Communicate! Liberate!” deals with. In it, a charismatic college professor manipulates radical students into rebellion on their campus. Central to the story are questions of hypocrisy and political radicalism, not least of which are the dangers of shutting yourself into an echo chamber. This was in October 1970, just in case you thought Oates was leveling criticism at modern college campuses.

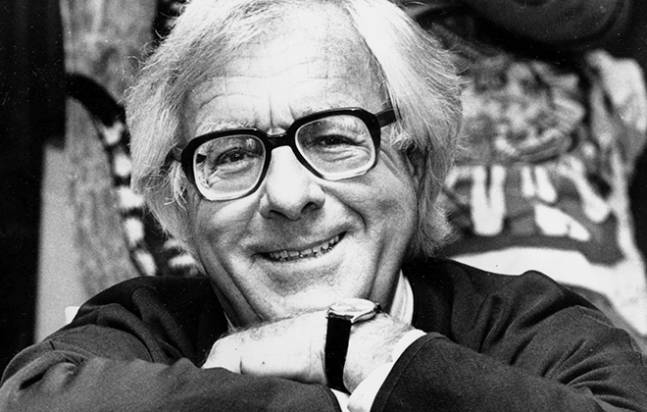

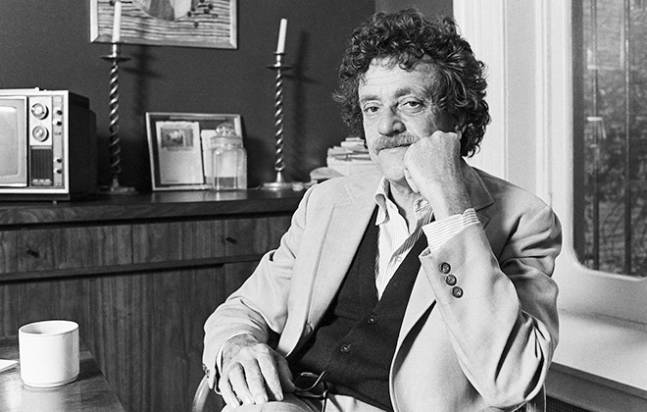

Kurt Vonnegut

Story to read: Welcome to the Monkey House, published in 1968

Any of Vonnegut’s work that includes his character Kilgore Trout includes mention of how Trout could only seem to get his science fiction published in smutty magazines. It only takes half a brain to notice the similarities between Trout’s career and Vonnegut’s, especially considering how open Vonnegut has been about Trout’s autobiographical nature. Playboy was a good partner to Vonnegut throughout his career, most of which was spent trying to fight the negative view people had of sci-fi. Arguably, the most famous story he published in Playboy was “Welcome to the Monkey House” in the January 1968 issue, which would later become the titular title in a highly successful short story collection. Fun fact: Ray Bradbury also had fiction in the January 1968 issue.

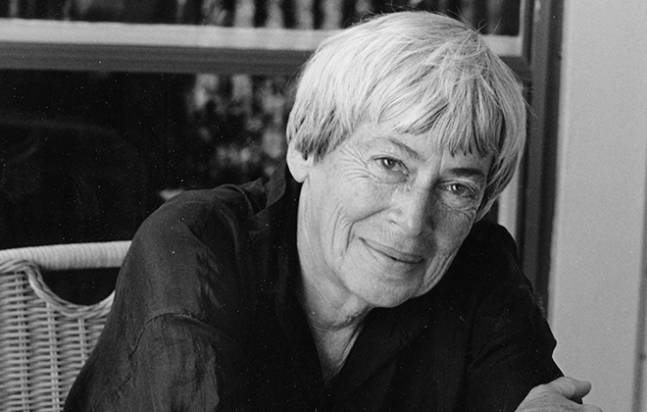

Ursula Le Guin

Story to read: Nine Lives, published in 1968

Ursula Le Guin’s entry to Playboy ends with Playboy reinforcing the publication’s pledge to elevate the social conversation, even if they had to compromise with sexism of the era. Le Guin’s agent sent off Le Guin’s “Nine Lives” to Playboy under the distinctly unisex initials U. K. Le Guin. The story was accepted and the Playboy staff was surprised to find out U. K. Le Guin was a woman. They still wanted to publish, but thought it would be more prudent to play the same trick on their readers that Le Guin’s agent had used. That is, they wanted to use her ambiguous initials, rather than print a female name. Le Guin agreed, and when Playboy asked her for an author’s biography, she considered sending a fully fictional one for a male writer. Instead, it simply read: “It is commonly suspected that the writings of U. K. Le Guin are not actually written by U. K. Le Guin, but by another person of the same name.”

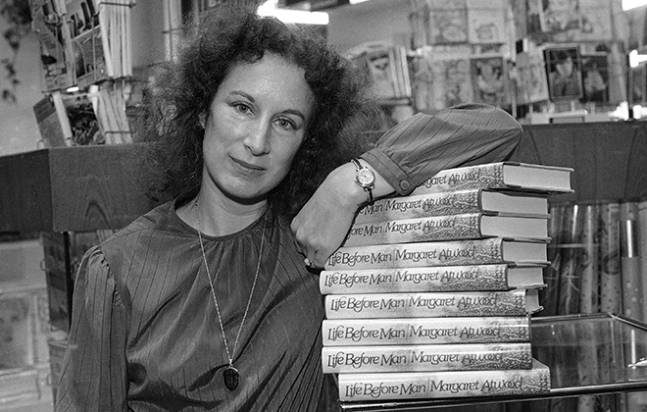

Margaret Atwood

Story to read: The Bog Man, published in 1991

You might not expect the author of The Handmaid’s Tale to be a recurring name in Playboy, but it seems Atwood follows the Joyce Carol Oates school of thought in that she didn’t want to completely ignore Playboy’s potential. She’s had a few stories in the magazine, but “The Bog Man” is one of the most famous. It’s an engaging story of infidelity, feminist psychological exploration, and sexual relations based around characters who lack the vocabulary to talk about all three topics. For example, the pull quote at the top of Playboy’s online version of the story is, “There was no such phrase as ‘sexual harrassment’ back then, no such thought.”

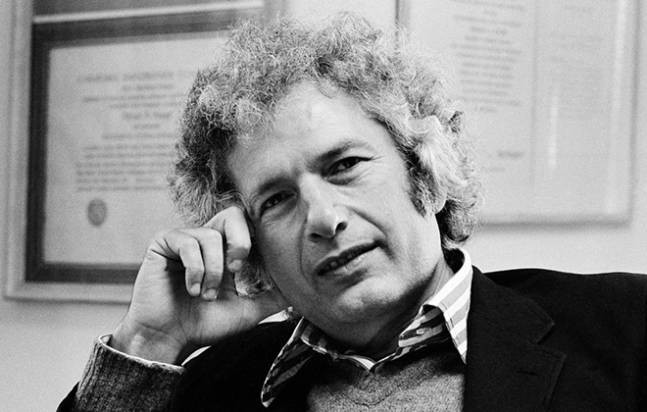

Joseph Heller

Story to read: Yossarian Survives, published in 1987

Joseph Heller has some conflicting memories about Catch-22’s editing process. He was absolutely sure that nothing got cut when he was putting together the manuscript for publication. He was also sure that he didn’t write a scene about phys-ed in the army. Neither was true, as proven by two officers from the Air Force Academy when they wrote to Heller asking why the phys-ed chapter wasn’t included in the final novel. Heller reexamined the chapter and couldn’t remember why it was cut, so he got it published in Playboy as “Yossarian Survives,” as well as published it in his short story collection Catch As Catch Can. This wasn’t the only time he did this. “Love, Dad” was another chapter that was cut and later published in Playboy and included in the collection. Heller agreed with both cuts, saying they helped make the novel more coherent, but that both were still worth sharing.

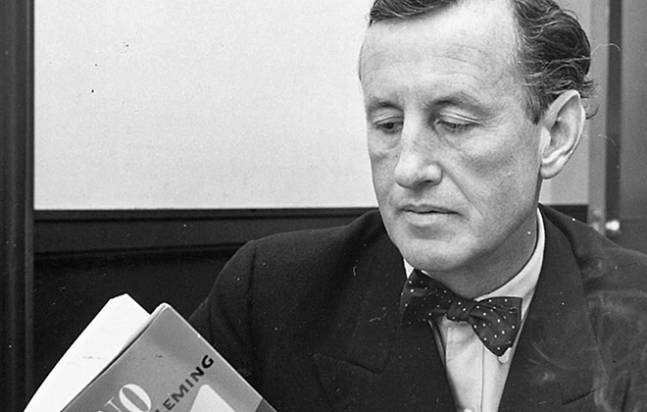

Ian Fleming

Story to read: The Hildebrand Rarity, published in 1960

Based on the popular romanticized image of James Bond (the one where he’s a globetrotting, smooth-talking gentleman with great taste in cars and suits), the pairing of Bond and Playboy is a natural one. Bond is a modern man with nuanced taste — the very same kind of man Hefner was trying to reach with his magazine. It follows, then, that Bond appeared in the March 1960 issue of Playboy with “The Hildebrand Rarity,” which brought the first taste of Bond to the wider American market. There’s been more Bond in Playboy over the years, with more short stories in 1963 and ‘64, along with the serialized version of You Only Live Twice running from April to June of 1964. There was also a posthumously published interview with Fleming in the December 1964 issue. In 1966, Playboy serialized two more novels: The Man with the Golden Gun and Octopussy.

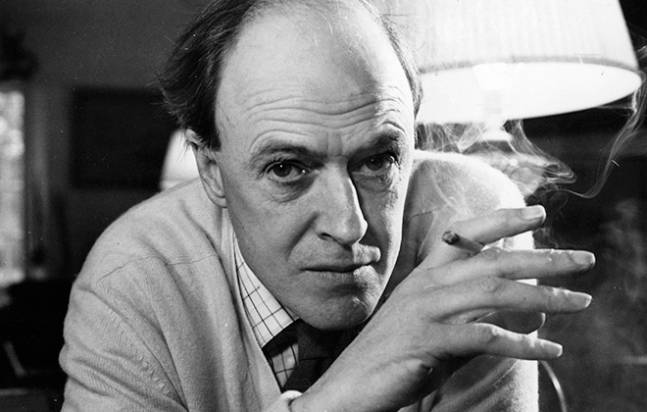

Roald Dahl

Stories to read: Switch Bitch, published from 1965 to 1974

Roald Dahl’s adult fiction career is similar to Dr. Seuss’s time as a propaganda cartoonist. It’s a piece of trivia a decent number of people know, but possibly don’t understand the extent of the work. Between 1965 and 1974, Dahl had four stories published in Playboy, all of which have been collected in the book Switch Bitch. They’re on the racier side, dealing mostly with sexual indiscretion. It’s an odd feeling to read erotic fiction from a man who’s more known for books about children finding unexpectedly large friends and living inside fruit. These stories are also by no means the only adult fiction Dahl ever wrote, they’re just the only ones that appeared in Playboy. As noted in The New Yorker, Dahl’s adult fiction has the same absurd quirks as his children’s fiction. Anyone who was a fan of the latter would find a lot to like in the former.

Chuck Palahniuk

Story to read: Guts, published in 2004

You know Chuck Palahniuk’s name because you’ve either read or seen Fight Club, but you should also know him just as much for “Guts.” He’s too good to be dismissed as a shock jock, since shock jocks rarely have anything of substance beneath their attempts at entertainment, but “Guts” relies on some of the same visceral reactions on behalf of the reader as Fight Club. It’s a truly disgusting story that accomplishes exactly what it sets out to do: remind you that even the most open and shameless among us have personal stories we won’t tell.

And, seriously, massive content warning on that link above. The story deals with masturbation and body horror. If you choose to click through and read the story, know that you’re in for a wild ride that’s truly unlike anything else on this list. At last count, 73 people have fainted at live readings of this story.

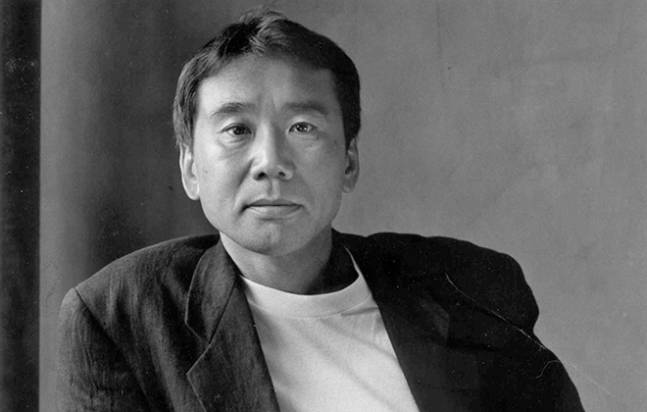

Haruki Murakami

Story to read: The Second Bakery Attack, published in 1985

One of the throughlines we’ve seen in Playboy’s choice in fiction is that the editors rarely like things that are completely straightforward. There’s a strong preference for fiction with some kind of absurdity or surreality, along with a penchant for genre fiction. That preference holds for Haruki Murakami, whose prose is rarely overly complicated, but whose subject matter and plots generally vear off into the odd. “The Second Bakery Attack” is no exception. The couple in the story are starving and anxious about where their next meal will come from when the man tells his wife about the time he and a friend robbed a bakery to feed themselves. The wife likes the idea and their search for a second bakery ends up taking them places they really would have preferred to avoid, a fact that they politely tell their unlikely victims.