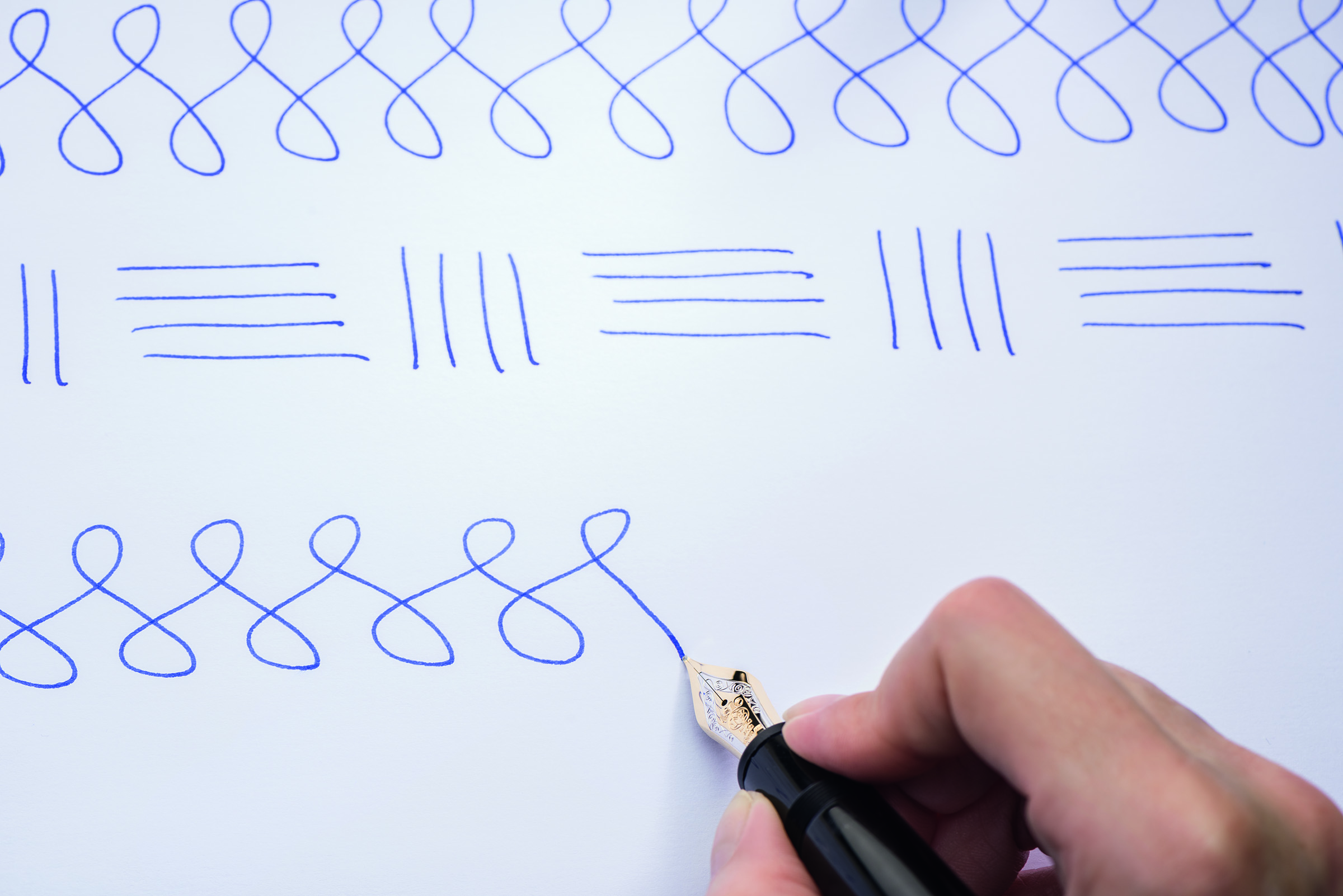

I was a writer without a pen. Worse—I was a writer without penmanship.

Though handwriting doesn’t have much of a role in the world anymore, I still have a journalist’s fantasy of doing things the old-fashioned way: scribbling on the sides of stories when making edits, taking notes in a Moleskine while reporting, scratching down quotes from sources on any piece of paper within an arm’s length. By the time I came to work for magazines, though, handwriting was almost entirely on the way out; now, the Notes app is where I keep my notes, the Docs app is where I keep my docs, and edits are convenient “comments” in the cloud. It’s not just a digital world we live in; it’s an almost aggressively anti-analog one.

Lately, this has come to feel like an uneasy arrangement. I believe in the power of tangible things—screenless objects you can touch, feel, and fuss around with. And I believe those things should be made with care and with substance. Craftsmanship—a sense of character—matters. Why should it be any different when it comes to writing? Yet most of what I kept around my house were cheap little plastic pens I picked up for free at my bank or dentist. As far as penmanship is concerned, I keep a journal by hand … but the best I can muster is something barely legible, sentences almost never written in an exactly straight line or with any sense of aesthetic consistency.

I decided it was time to grow up. I went to the most grown-up place I could go: Montblanc, the famous and fabulous creator of the most beautiful pens in the world.

It was the 100th anniversary of Montblanc’s most iconic model, the Meisterstück, and the date felt like some kind of celestial sign: If Montblanc’s old-world ink pen could persevere for 100 years—into the age of Kindle and the New York Times app—there’s something of real significance here. A century of success does not lie.

Montblanc was founded in the first decade of the 20th century in Germany. In 1924 came the Meisterstück, the German word for masterpiece. Shaped like a small cigar, it quickly became the gold standard for pens. (Incidentally, portions of these pieces were crafted in actual gold.) Iris Murdoch, the novelist, drafted all her works with a Montblanc fountain pen; Salman Rushdie is said to still use one; and when James Bond is given a gadget-laden pen by MI6, you can bet it’s a Meisterstück.

With the Meisterstück in hand, there is a newfound sense of purpose in my writing.

The classic Montblanc Meisterstück is a fountain pen, featuring that iconic nib with a sharp point for writing. These days, you can buy one with an ink cartridge inside, but you can also dip Montblanc fountain pens into a bottle the old-fashioned way. For my first foray into proper penmanship, though, I chose a rollerball, which is less authentic to the 1924 experience, maybe, but a convenient instrument for the modern age. I want to be able to throw this pen into a tote bag and scribble quickly while on the move, which is certainly possible with a fountain pen … but probably a little less sensible.

In this digital age, when things can often feel superficial and rushed, handwriting allows me to go deeper into my thoughts.

The shape and feel of the pen in hand is sublime. The new pieces are as expertly built and pleasing to the eye as the old ones. “When something like this has been created, you don’t want to touch it or tamper with it because it’s perfect in terms of proportions and aesthetics,” Vincent Montalescot, Montblanc CMO, tells me. “Its status as an icon means you can’t change it. Beyond its physical beauty, it is a functional object that delivers a heightened writing experience, an object that has meaning and is handed down through the generations.”

The precious resin with which Montblanc makes their pens is hearty and black; it feels solid in the fingers. Something this gorgeous doesn’t get tossed into an old mug on my desk for storage along with my bank pens; I proudly display it on my coffee table. I like the way you have to unscrew the cap instead of sliding it off—it makes writing feel like an activity as opposed to an afterthought. “Writing by hand is simply a different experience than texting or drafting an email,” Montalescot explains. “It’s a ritual that forces you to slow down. That can perhaps be intimidating to some. Because you can’t instantly delete it or rewrite it, you become more intentional. Ink on paper is permanent, and that’s where the deeper connection comes from.”

I can’t say if Montblanc alone has elevated my penmanship, but I do know that style is about intention, and with the Meisterstück in hand, there is a newfound sense of purpose in my writing. “In this digital age, when things can often feel superficial and rushed, handwriting allows me to go deeper into my thoughts,” says Montalescot. He tries to articulate what he’s feeling in a more meaningful way—to “think and feel differently, rather than just being on autopilot.” That’s what the Meisterstück has meant to me: If we’ve all been on a slow gravity drop toward the digital, with the Montblanc, we can be deliberate about writing a slightly different story.

More Features

Black Book: 13 Products Our Editors Loved in February 2026

The products our editors have been obsessed with in February 2026.

This Is Alberta Before It Was a Postcard

My four-day Indigenous-led road trip through Jasper and Métis Nation territory, mapped.

The Sundance Film More People Should Be Talking About

It's called Filipiñana.