German beer purists would have you believe beer was divinely begotten from malt, water, hops, and nothing else. If it wasn’t divine, then it was at least bureaucratic, thanks to the Reinheitsgebot, a law that regulates beer production and has for more than 500 years. It’s a law so old it predates the discovery of yeast, which you’ll remember is what actually makes beer alcoholic.

Nothing against the Germans here. Their beer styles are synonymous with high quality and some of our favorite days have been spent in German beer gardens in America and Germany alike. German beer is an invaluable contribution to drinking culture and it’s amazing the ingenuity Germans have shown when they’re that limited on potential ingredients.

But there are plenty of beer drinking cultures not governed by the Reinheitsgebot and their history isn’t as widely publicized. They were using all kinds of different flavors and aromas to make their beer distinct, delicious, and wholly unique, without a hop in sight.

Thousands of Years in Four Paragraphs

There doesn’t seem to be a solid origin date for beer. Speculation and educated guessing puts the first fermented drinks around twelve thousand years ago, when nomadic tribes started settling down and becoming agrarian civilizations. Staple crops haven’t changed much since then (we’re still eating a ton of corn, rice, barley, and wheat) and it wouldn’t take much for someone to stumble upon the fermentation process. In fact, if we can contribute a bit to the speculation, we find it unlikely that there was ever a formal invention process for beer.

The first written recording of beer as we’d (kind of) recognize it comes from Sumeria in Lower Mesopotamia a little more than five thousand years ago, in a document that’s a sort of half recipe, half prayer. Ninkasi was a Sumerian goddess whose name translates to “lady who fills the mouth.” In other words, she was the goddess of bread, though her other major contribution was the invention of beer and the education of mankind in the ways of brewing.

The earliest mention of hops as an ingredient in brewing doesn’t pop up until thousands of years later. In 822 A.D., in Picardy, Northern France, Abbot Adalhard of the Benedictine monastery of Corbie recorded rules for the proper functioning of his abbey. In those rules, he mentions guidelines and requirements for the collection of wild hops for brewing. Germany didn’t adopt hops for another three hundred years.

For anyone doing basic math at home, a drink we would recognize as and call “beer” existed without hops for at least four thousand years, though that number could be closer to eleven thousand. That’s a mind-bogglingly long time for beer to exist without hops. What’s more, it means hop purists are actually historical anomalies with a fierce devotion to one of the youngest aspects of brewing.

Drinking Like the Neolithic Scots

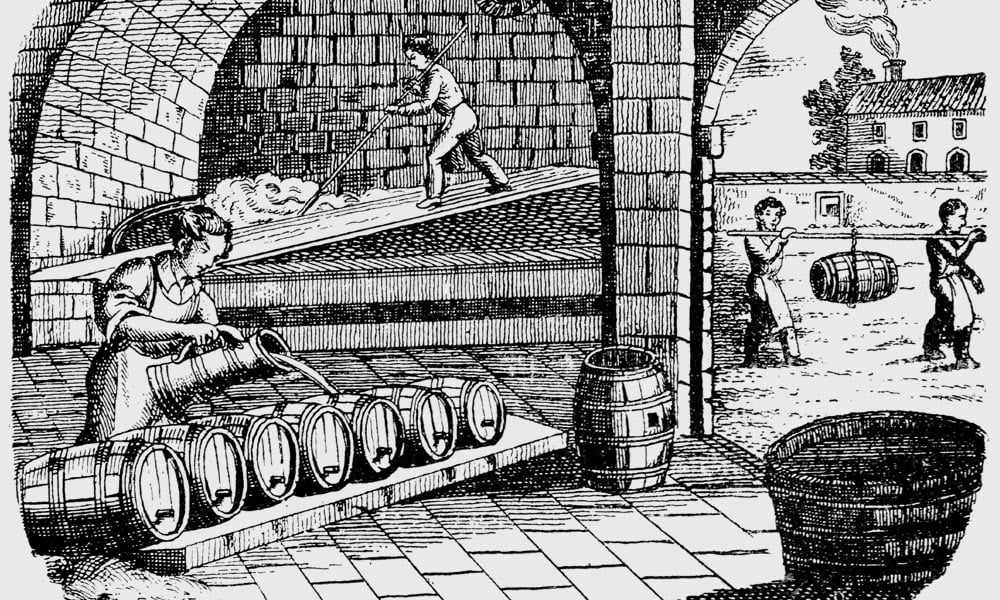

One of the oldest ale styles still in some form of production is the Scottish Heather ale. There’s evidence that people were brewing it roughly five thousand years ago on the Orkney Islands off the Northeast Coast of Scotland. Most of that evidence comes from archaeological digs in Neolithic settlements. In the settlements, pottery shards yielded grain, heather, fern, and pollen residue, all confirming the existence of fermented brews. These were also supposed to be the magic potion that kept the Romans from getting deeper into Scotland all those years ago.

The heather tips are added during the boil, the same way hops are, and the end result is a heavy, dark, full ale that’s much, much closer to a Scotch Ale than anything else. In fact, it’s highly likely that the mildly popular Scotch Ale is just the Heather Ale modified to slightly fit with modern drinking sensibilities. Modern craft brewers in Scotland are keeping the style alive, and seeing as how there still aren’t any Romans in Scotland, the drink seems to still be working.

Gruit Ale: An Herb Garden in a Glass

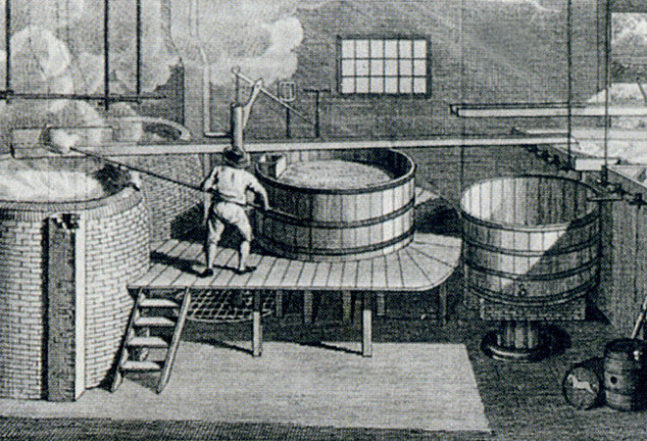

While it’s absolutely true there were ancient brewers that didn’t bother making their beer with anything beyond malt and water, there were plenty of them who were flavoring or aromatizing their beer with local plants. This beer was known as gruit ale and was traditionally made with bog myrtle, yarrow, and wild rosemary. Depending on where you are, these three herbs are fairly common. Common enough at least that people knew what they were looking for, never hurt for supply, and liked their taste well enough to keep the plants around.

Surprisingly enough, gruit ales have their roots in German culture. The word “gruit” comes from the German word “grut,” which means herb. As far as we can tell, there’s nothing wrong with Germans brewing gruit ale. They just won’t legally be allowed to call it beer.

These ales fell out of favor mostly because of the tendency of random herbs to add different effects to beer. Depending on types, quantities, and mixtures, gruit ales would occasionally change their effects from simple drunkenness to something more devious. Usually any effect would simply intensify the intoxication, but some brews were known to push into the psychotropic.

Gruit didn’t start to fall out of favor until the Protestant Reformation, when a temperance movement began to grow as a reaction to Catholic indulgence. Protestant reformers saw gruit ale as yet another area of sin and corruption that was dragging the Catholic faith towards ruin. They also found unlikely allies in businessmen and royalty. It wasn’t that the latter two supported the temperance movement. Instead, they wanted to break the monopoly the Church had on gruit production. When they finally did, they also mortally wounded a millenia-old drinking tradition in Europe and ushered in the limitations of hopped beer.

Ben Franklin’s Personal Spruce Recipe

On one of Benjamin Franklin’s many overseas excursions, he jotted down his “Way of Making Beer with Essense of Spruce.” It’s an odd recipe and one that takes a few liberties with what you can call a “beer.” The sugars come mostly from molasses instead of any kind of grain, along with the lack of hops we’ve been talking about all this time.

One of the benefits of using spruce in your beer is how surprisingly healthy spruce is. There’s a decent amount of Vitamin C in it, which you presumably don’t lose much of if you use it in brewing. Spruce also grows easily all over the place and doesn’t come with the same restrictive climate needs hops have. Both those together mean you could whip up Franklin’s recipe for extra cheap and in large amounts. And if you did that, you could, say, keep the army of a burgeoning nation on its feet and relatively healthy.

This is a beer you can drink today too, with a few updates made to reflect the current market (i.e. less molasses and more grain). Yards Brewing Company in Philadelphia put together an Ales of the Revolution series, in which they sell three beers inspired by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin. Washington and Jefferson’s are both great beers, but they’re disqualified from inclusion in this article thanks to the inclusion of hops in their recipes.

Poor Richard’s Tavern Spruce, however, includes no hops in its modern recipe and is a great introduction to beer without hops. It’s a heavy but easy to drink ale, with strong caramel malt and intense spruce flavors. It was the first hopless beer we ever knowingly tasted and is what started us on the journey that’s culminated in this article. If you can find the Tavern Spruce near you, we highly recommend you pick it up. It’ll help show you beer can afford to lose the hops sometimes.