Road trips are one of those things that are initially planned and constantly postponed. We’ve had a road trip to Nashville and/or New Orleans planned for four years now. And don’t bother pitying us. We know that’s as common among our readers as it is here in the office.

That’s a fairly new phenomenon though. As crazy as it might sound, there was once a time when people actually took the trips they planned. Families and friends would pile into the tanks American companies used to call cars and careen across the newly constructed interstate highway systems, stopping for photo ops with the world’s largest turnip as often as they stopped at the Grand Canyon. Cramped, sweaty station wagons were one of the defining features of the American vacation and are now strictly relegated to the pantheon of cultural nostalgia.

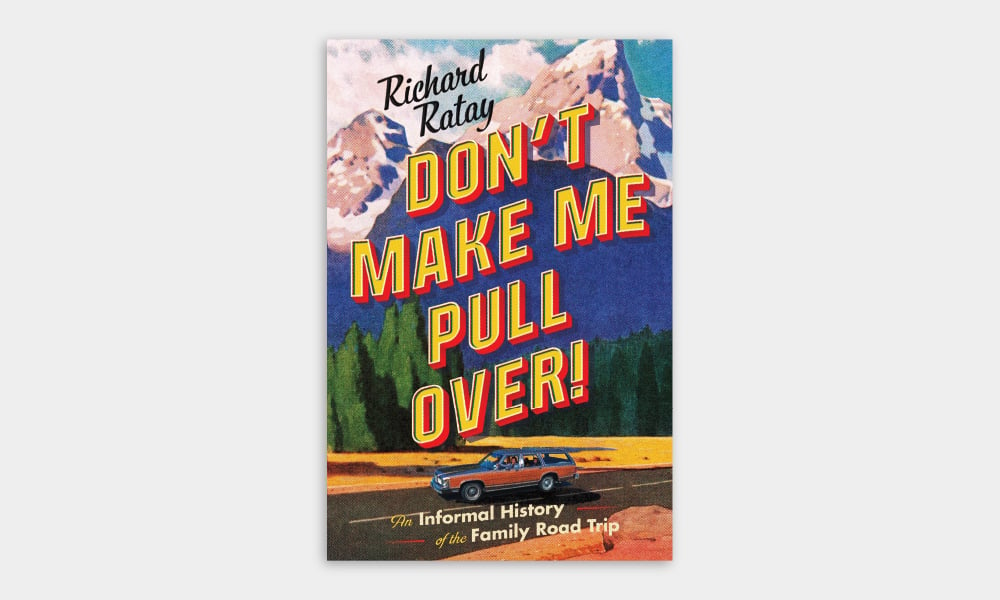

Don’t Make Me Pull Over! is Richard Ratay’s attempt to record the history of the iconic vacation. He blends historical fact with his own personal experiences in the car, creating an image of both familial bonding (or unbonding, depending on the trip) and the country’s evolution in and defining of the mid-twentieth century.

It takes a deep look at all aspects of the road trip, including how the rapid development of Eisenhower’s highway system allowed Americans to connect with much more of their country, what increased tourism did to the national park system and historical landmarks like the battlefield at Gettysburg, and what the trips did to foster the closeness of nuclear families that remains so important to the idyllic (though now controversial) American Dream.

The book also promises to examine what the modern demand of, as they put it, “getting there now” has done to the average American family, its sense of togetherness, and the vacations they take. It’s not a unique observation when someone says modern technology and cheap airfare have changed the foundation of a family’s vacation, but Don’t Make Me Pull Over! is one of the first to put empirical evidence to the claim and really challenges the idea that change is true progress.

It seems to be Ratay’s hope that, by the end of his book, the reader will use re-examine their modern vacation through a nostalgic lens and ask if a modern vacation—with its insanely fast air travel, buzzing phones, and electronic maps—is truly the best way to travel. $24