For brewing and distilling, these are days of revival. Brewing was a macro-lager mess up until a few years ago, when craft brewing exploded, giving us roughly ten million choices in even the smallest liquor stores. Craft distilling is seeing a similar revitalization. Where we once had only a few enormous brands to choose from, liquor store shelves are now filling up with independently produced whiskeys, vodkas, gins, and rums. Spirit enthusiasts haven’t had this much choice in a century.

One of the major components of the craft distillery movement has been, and continues to be, rye whiskey. Historically speaking, rye has the deepest roots in American distilling. We’d never stop you from enjoying a great bourbon, but for drinkers who want to immerse themselves in American distillation culture, rye whiskey is absolutely mandatory.

In a way, rye whiskey is the mirror image of bourbon. It follows similar rules as bourbon, but does so with different ingredients. Where bourbons tend to be sweeter and smokier with hints of caramel, rye whiskey is spicier, including notes of pepper, grass, and grain. Just as bourbon must be 51 percent corn, to be considered American Rye, the spirit must be 51 percent rye grain, though, like bourbon, most expressions will opt for something higher. Furthermore, rye can be distilled no higher than 160 proof, aged no higher than 125, and bottled no lower than 80. Barrels are much the same as bourbon barrels, in that they are newly constructed, charred oak casks.

Where rye differs from bourbon significantly is in its history. It’s not a history soaked in blood, like moonshine, or rooted in the American slave trade, like Jack Daniels. It’s more a history of a spirit that went from a near monopoly on American imbibers to little more than an alcoholic footnote to driving the cocktail revival of roughly the past decade. The history of rye whiskey is a story about how quickly you can rise to fame and fortune in America, how quickly you can lose it, and that total destruction doesn’t mean you should be completely counted out.

Early History

The two main states we’ll be dealing with in this section are Pennsylvania and Maryland and we’ll borrow a bit from our Moonshine article and say Pennsylvania and Maryland got such huge distilling operations because that’s where Scotch-Irish immigrants settled. Both Scotch and Irish whiskey are made using primarily barley, but barley didn’t adapt well to the new climate of North America. Rye, however, did.

When they got here, the immigrants would build themselves small stills to continue their long distilling tradition, using the rye they grew on their modest farms and accidentally inventing an excellent new American spirit. From there, whiskey production went from small, private operations to large, commercial productions.

Both Maryland and Pennsylvania were seen as the premiere producers of rye whiskey. Pennsylvania’s premiere style was Monongahela Rye, a whiskey named for where it was first made, in the valley of the Monongahela River. Supposedly, the whiskey gained its reputation by accident. Aging the whiskey was a product of necessity, not something the distillers did on purpose. Shipping the whiskey took a long time before the age of steamboats and motor vehicles, so the necessary storing and travel time meant the whiskey could be two years or older by the time it finally reached its destination.

Maryland’s version of rye mixed more corn into the mash, making it a sweeter whiskey, slightly easier on the palate of the less initiated. It was easier to drink, but no less a rye whiskey than anything made in Pennsylvania.

The Rise

After the Revolution, rum wasn’t as widely available, seeing as how the newly established country just fought a protracted rebellion against the largest naval power in the world. Since rum is made of molasses, molasses is made using sugar cane, and sugar cane was only widely available as a Caribbean export, the liquor wasn’t making its way to America. This left a vacuum in the spirit world that Americans felt almost immediately.

At the same time, the Scotch-Irish immigrants we mentioned earlier had perfected their craft, turning it from a local operation into something that was ready to supply something far larger. They jumped at the opportunity to fill the gap left by rum and urban populations enthusiastically bought up the new whiskey. An American spirit for the new America. Pennsylvania rye began to make its mark.

Quickly, the mark became profound. This was whiskey production at levels that would boggle modern rye drinkers’ minds. In 1810, Kentucky made 2.2 million gallons of bourbon, a perfectly respectable whiskey with deep ties to American distilling history. That same year, Pennsylvania shipped 6.5 million gallons of mostly Monongahela rye, nearly three times as much. That’s a drastic disparity between what bourbon distillers market as the quintessential traditional American whiskey and what Americans actually drank.

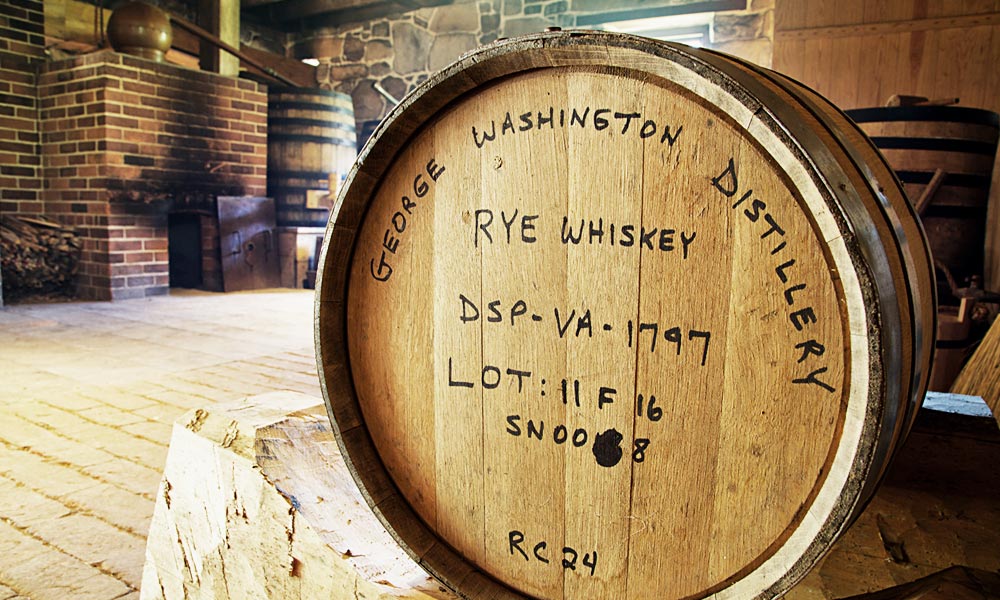

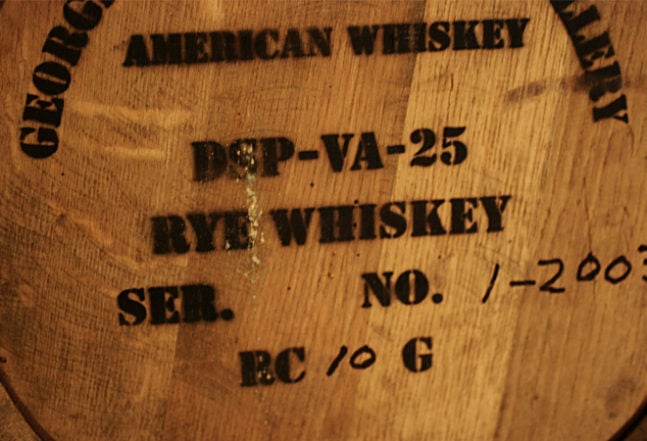

Rye whiskey was so ingrained in the American psyche that George Washington ran his own distilling operation in the late 18th and early 19th century. It was a small operation by today’s standards, when huge distilleries run productions in the millions of gallons, but by contemporary measurements, George Washington was a veritable whiskey tycoon. His five still, 11,000 gallon production was an enviable one, and modern consumers are again flocking to Mount Vernon to get a taste of Washington’s whiskey. That’d be like Obama leaving the White House and opening a craft beer operation akin to Yuengling’s current output. And having it be just as successful.

There might be some doubt as to the credibility of these claims, as rye isn’t easy to drink straight like bourbon, Scotch, or Irish whiskey. Its flavors can overwhelm or alienate drinkers who are more accustomed to sweeter, smoother spirits. But drinking it straight wasn’t the only way people consumed the whiskey. In the 1800s, people were mixing cocktails and plenty of them. The Manhattan, Old Fashioned, and Sazerac all used rye as their base alcohol, and all were insanely popular. Modern speakeasies would salivate at the chance to mix drinks in the volumes the people of the 1800s did.

This emphasis on cocktails and mixed drinks carried straight through to the 1900s, when rye whiskey’s empire was going to get its first real challenge since it came out of Pennsylvania and Maryland. But these challengers weren’t going to be another kind of alcohol. They were Prohibition and two World Wars. It wasn’t going to go in rye’s favor.

The Fall

Prohibition’s role in the rapid decline of rye whiskey isn’t much of a surprise. As a grain and a whiskey, rye is one of the more expensive and intensive to produce. If plenty of people are buying it, or you’re distilling as a personal operation, that expenditure of money and effort don’t affect the process too drastically. You have a pretty stable operation, so you can make an affordable, delicious whiskey.

But the moment the federal government decides your product is not only illegal, but unconstitutional, your little distilling operation becomes far more problematic. That’s exactly what happened to rye. It’s market collapsed almost overnight, just like the majority of American breweries and distilleries at the beginning of the 20th century. And true American rye was more expensive to produce, Canadians apparently aren’t such sticklers to mash standards. Canadian whisky, just like now, could be called rye, despite not actually requiring rye to be an ingredient in the mash. Rye became the equivalent of bottom-shelf, frat party vodka.

Beyond the economics of supply, demand, and illegality, rye also took heavy flak from contemporary pop culture and its previously great name was dragged through the deepest mud Hollywood could find. It went from everyone’s favorite whiskey to what drunkards and layabouts drank on their never-ending quest for a quick, cheap fix. Rye was put in the hip flasks of 1930s gangsters and got Ray Milland black out drunk in the 1945 film The Lost Weekend. It was some seriously bad PR for a whiskey that couldn’t afford it.

A few distilleries survived, particularly in Maryland. Since Maryland never ratified the 18th Amendment, it would appear the state government never put a lot of energy into enforcing it. Some Maryland distilleries produced medicinal whiskey (pretty much the exact same way people get weed for their “glaucoma”), while other simply didn’t call attention to their moonshining.

Let’s move on from Prohibition to something we talked about earlier. Bourbon distillers would love for you to think corn whiskey made to their specific standards is the pinnacle of the American distilling tradition, and it absolutely deserves the popularity it’s enjoying right now, but the truth behind its popularity isn’t quite so romantic as marketers would have you believe. It’s riding a cultural wave created by the perfect storm that wrecked rye whiskey.

Just before and after Prohibition, during the First and Second World Wars, the US government subsidized corn, making it a far more enticing crop for farmers. Corn got cheaper and more available, while rye retained its inherent expense and difficulty. Distillers flocked to corn before Prohibition to make a quick buck and after to reestablish their industry. It was a pragmatic business move more than a deep seated respect for traditional American distilling.

After the world stopped tearing itself apart and American consumers could refocus on alcohol, they started buying up vodka and gin, thanks to a certain smooth talking British secret agent. Vodka and gin drinks became the sign of classy drinkers and people eschewed brown liquors that weren’t bourbons or Scotches. By the 1980s, rye was the drink of Don McLean’s aging alcoholics.

It was a sorry end for a whiskey that had spent nearly two hundred years as Americans’ whiskey of choice and three hundred as Western Pennsylvania’s proudest product. But history has a tendency to rectify this level of injustice and a new generation of cocktail enthusiasts were about to discover what rye whiskey can do for the experimental mixologist.

The Rise (Again)

Just as everything in history is cyclic, rye whiskey is roaring back onto the bar scene. Relative to other types of whiskey sales, rye is still dwarfed, but rye’s volume is up more than 500 percent since 2009, a figure that wildly outpaces the growth of those other whiskeys. Big brands like Jack Daniel’s and Jim Beam have noticed and launched their own rye expressions, while Wild Turkey’s was so popular they nearly completely ran out.

Other craft distillers have taken notice, with Anchor Distilling actually having the foresight to establish their rye 18 years ago, beating even Mount Vernon to reviving George Washington’s styles. These are whiskey’s made from purely rye mash and only lightly aged, if at all, just as the earliest versions of rye were sold. They’re sharp, herbal, sweet, and basically clear, perfect for taking your cocktail game back to basics.

Buffalo Trace (not exactly craft distilling, but their experimental stills kind of qualify), provided the rye that made the Sazerac famous in the 1800s and has relaunched their brand. Sazeracs, Old Fashioneds, and Manhattans all enjoy a more nuanced flavor when made with rye, and people are noticing. Plus, as soon as you say something is more suited for the “experienced drinker” millions of people decide they’re old pros.

We already talked about Mount Vernon’s distilling operation, but we might as well reiterate. They make their whiskeys with the results of their research into George Washington’s own recipes. They’re more than happy to talk about the history of their distillery and alcohol in America, and a whiskey tasting with them automatically puts you one step closer to having wooden teeth and an undying love for colonial independence.

Surprisingly though, not all the established brands are experiencing a rebirth. Old Overholt, one of, if not the, most oldest names in rye whiskey, hit every beat of rye’s life in America except for the modern twist. They were huge in the 1800s, were gutted by the World Wars and Prohibition in between (despite having a “medicinal whiskey” permit), were forced to turn their whiskey in cheap, diluted rotgut, was overshadowed by vodka for much of the later half of the 20th century, and was eventually bought by what became Beam Suntory. But instead of jumping back on the shelves and into cocktails, Old Overholt is in a sort of limbo. Beam Suntory isn’t completely convinced that the rye revival is a credible movement, so they’re leaving some of their rye brands in the background, Overholt being one of them. Hopefully a year or two more of solid sales means the brand will come back.

Rye’s resurgence can largely be attributed to something you are undoubtedly intimately familiar with. Bartenders and their customers are getting more adventurous. They started with an authentic Manhattan and moved out from there, crafting more and more cocktails on the spicy backbone of flavorful ryes. People go to mixologists for experimental flavors, not watered down vodka drinks.

New distilleries are also eager for the chance to make their mark with an unknown type of whiskey. They see in rye and opportunity to get in on the ground floor of the revival of a whiskey with distinctive flavors. People love the new taste, and if these distilleries can create a memorable rye, they can count on a few years of fierce brand loyalty. With more people mixing rye based cocktails at home and requesting specific brands at bars, distilleries want to make sure they’re the ones being asked after.

Where bourbon was at the beginning of its renaissance, rye is now. It was within our lifetimes that century old bourbon brands were struggling to make an impact on the public. Now, bars have shelves devoted to bourbon and only bourbon. It’s not inconceivable that, a decade or so in the future, we’ll see dozens of ryes taking up a serious amount of that space.