Whiskey is ripe for experimentation right now and distillers are switching up every step of the process. They’re using new grains, changing their casks, and taking the aging process mobile. Some of these experiments make for great new whiskeys, while others end up tasting like something you’d use in a medieval witch hunt. But you know what they say, nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Kikori Rice Whiskey

Our first few picks are going to be whiskeys made from grains that aren’t barley, rye, or corn. Not because using other grains is a wacky and wild thing to do, but because whiskey is so entrenched in tradition.

For Kikori Rice Whiskey, the only grain is rice. Previously, the only booze we’d heard of using rice was sake and Bud Light. The first one is a pleasant change of pace, the second one is a cheap filler, and neither one made us think about whiskey as a next logical alcoholic step. But rice whiskey is a smooth, easy drinking change of pace. It’s also something that’s been made in Asia for centuries, so we’re really behind the ball on this one.

The whiskey is made and aged entirely in Japan, meaning it’s a likely addition to our next iteration of a best Japanese whiskies article. Kikori is mostly available on the West Coast, so keep a lookout if you’re in California. Most bottles you find are going to hover around $35 to $50 each, so it’s not a terribly expensive whiskey if you can find it. Also, start shipping some bottles eastward. No one likes a selfish whiskey drinker. Buy

Koval Bourbon

Koval’s bourbon is legally a bourbon, with its 51% corn mash, but the distillers filled in the remaining 49% a bit differently than most distillers would. Instead of rye or barley, they’ve gone with millet. Millet is a huge grain in Asia and Africa, where they use millet the same way we use corn. Millet also has experience in distilling, though in Nepal.

The different grain also changes the flavor profile, as you’d expect. Koval’s flavors include mango chutney, if that’s something you can expect in a whiskey, vanilla, caramel, and a bit of tobacco. It’s a masterclass in bourbon technicalities, since it obeys all the rules you need for a bourbon, but ends up with flavors distinct in its class. They don’t all have to taste like varying levels of corn and rye.

We’ve actually featured them before too, though not quite with the same company they’re keeping on this list. Back then, it was bourbons you should try not made in Kentucky. $55

Dry Fly Triticale Whiskey

Triticale sounds like the perfect whiskey grain. It’s a hybrid breed of wheat and rye that’s supposed to capture the bold spice of rye and the softer subtleties of wheat, and sounds like the perfect whiskey to transition people from rye to softer types or from lighter whiskeys to the big flavors of rye. Kind of like if someone invented a gradient slider for whiskey instead of color.

Dry Fly Triticale Whiskey is straight triticale. They’re not trying to distract from the grain, use it as a filler, or lean on it as a marketing gimmick. It’s the only grain they’ve used and they’re confident it can stand on its own. Which, apparently, it can. Most reviews we’ve read, like this one from The Whiskey Wash, talk about how the whiskey delivers on its promise to exemplify the best flavors from both of its grain parents. The rye delivers some great character, while the wheat mellows things out and makes it easier to drink. Overall, that’s not bad for a grain someone invented to help stave off famine. $67

Cooper River’s Single Run Series Whiskey

It didn’t occur to us that whiskey is just distilled beer until we talked to James Yoakum, founder of Cooper River Distillers, and he told us exactly that, just in more educated terms. When you make whiskey, all you’re doing is refining a beer you didn’t put hops in. Distillers call it “wash,” but that’s because every industry needs its own words to feel special.

But it did occur to Yoakum, so he started calling up local breweries and asking if he could have the beer they didn’t want to sell or were just going to throw away. Usually it was experimental brews that didn’t pan out or beer that wasn’t quite up to the breweries’ high standards. Their Tuckahoe Porter was one of the most popular expressions, but they’ve also done IPAs, English milds, saisons, and an Oktoberfest. Because they’re using fully matured and brewed beers with their own unique flavors, each whiskey comes out with its own distinct character. The porters are deep and sweet and the IPAs are light and bitter.

The cool thing about Cooper River’s arrangement is they only have a limited amount of beer, so this isn’t a manufactured scarcity. They can only make a certain number of bottles with the supply they’re given, so once the whiskey’s gone, it’s actually gone. It’s not like when Jim Beam pretends their new experimental style is a limited supply, but then suddenly finds out they can actually make a million more barrels, coincidentally at the same time their whiskey sells out to rave reviews. If Cooper River says they have 100 bottles, they have 100 bottles.

Currently, their website lists every bottle as sold out. You might be able to visit and find one, but we tend to believe their online listings. But don’t worry. They have four more beer whiskeys lined up, so you’ll have more opportunities to try one out. Link

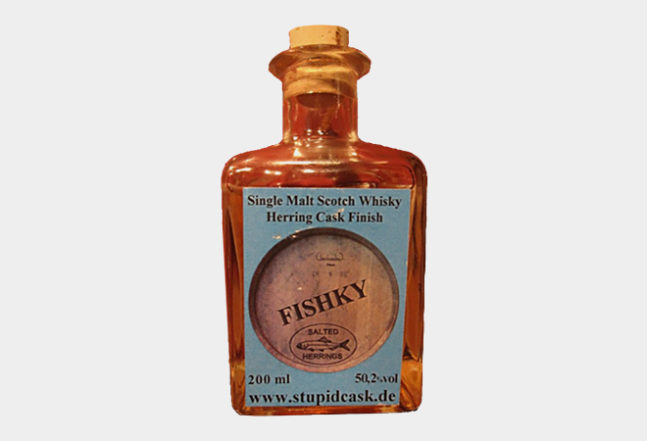

Fishky

Fish and whiskey aren’t a pairing that jump to the forefront of our minds. At the risk of sounding less than cultured, if we’re eating fish, we save the alcohol pairing for before or after, as the taste of fish tends to take over a meal. Decisively, at that. Wine might be the only thing that pairs well, and we’ll generally leave that process to Italian restaurants.

But apparently we’re not thinking outside the box enough, because someone thought it was a good idea to finish a perfectly good Scotch in herring casks. Apparently the idea comes from the story that Scottish sailors used to keep their shipboard whiskies in old fishing barrels. Whether or not that’s a practical solution is up to your own personal tastes (and how desperate you are for whisky), but the WhiskyCast review is not a good one. To sum it up, Fishky smells interesting, with some salty, briny notes to an otherwise average Scotch. But when you taste it, the herring takes over and not in a good way. In a way that tastes like the ocean is puking in your mouth.

And if that flavor profile is somehow attractive to you, good luck tracking this one down. We’ve only been able to find the WhiskyCast review, and there aren’t any shopping links or distillery names attached to it. There is a name for a bottler, but when we went to stupidcask.de, we found a German clothing brand. So unless Bavarian Urban Outfitters dabbles in whisky finishes, Fishky is quickly fading into urban legend territory.

Reindeer Antler Whiskey

Reindeer antler whiskey was featured here before, but it’s too unusual to not talk about twice. It’s an old Thai tradition that perfectly fits into modern times, since this is actually an infusion rather than a whiskey someone aged in a reindeer antler cask. The belief is that a reindeer whiskey infusion boosts vitality and all around good living.

It’s part of a larger tradition of Thai herbal liquors called Yaa Dong. These are herbal drinks and infusions meant to treat ailments or improve whiskey taste, so they’re not actually all that different from the European and American practice of whipping yourself up a hot toddy when you feel a cold coming on. In Thailand, you can find whole bars devoted to Yaa Dong, which would make your vacation to Thailand one of the healthier trips you could take. $5

Jefferson’s Ocean

Jefferson’s Ocean took a better route to ocean inspired whiskey than Fishky did. Instead of creating something people wouldn’t even age sardines in, Jefferson’s decided to make and cask whiskey like normal people, then age that whiskey on sailing voyages. That means the ocean’s influence is much more about climate than taste. On the voyage, temperature fluctuate wildly, salt air interacts with the barrels and whiskey, and the rocking of the boat sloshes the whiskey around. We’re not sure what the last part does in a technical sense, but since most whiskey is stuck on a shelf for years, putting some motion into the process definitely has to change things.

According to Jefferson’s, aging the whiskey on the ocean gives it characteristics you’d normally find in other spirits. The color and base flavors are closer to dark rum and the sea air injects some Scotch into an American bourbon. We’d imagine flavors also change based on the route and time of the year. Weather can change drastically on the ocean, so the products of different voyages should end with subtle differences. Or they’re completely different. We haven’t tasted them all. $85