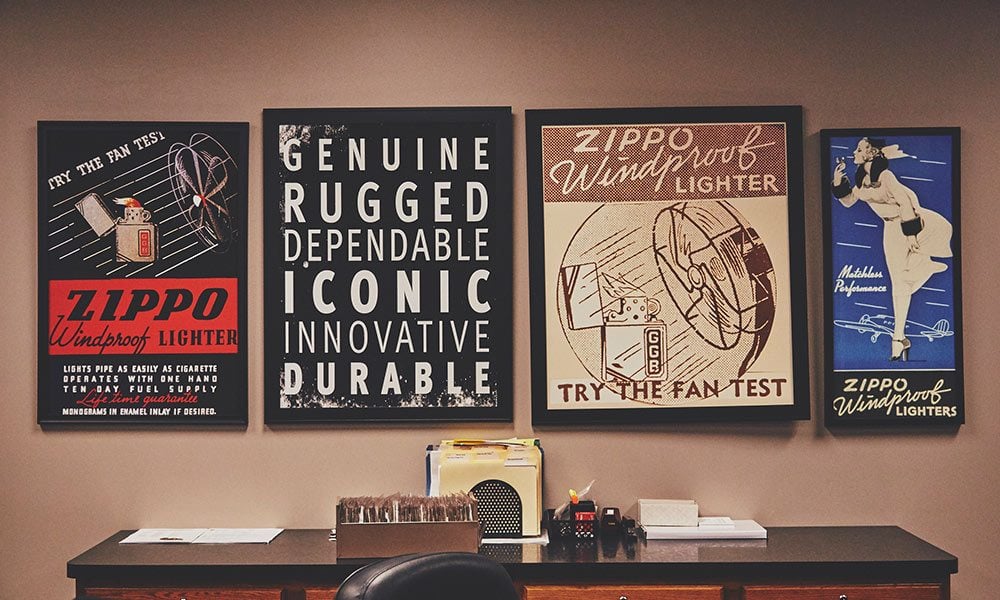

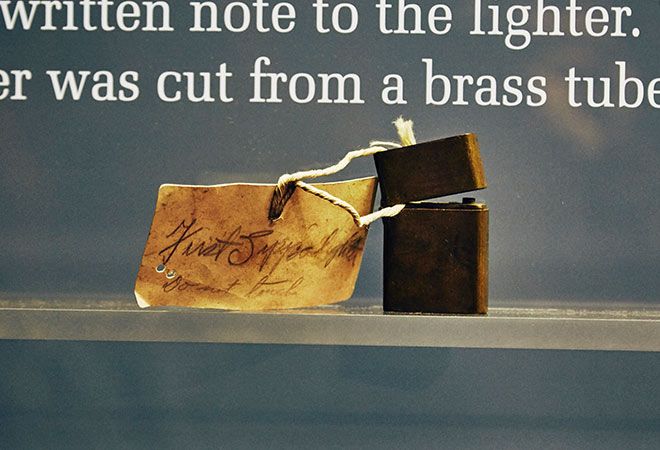

First, sell an item only a portion of the population needs. Second, slap a lifetime guarantee on it—not the customer’s lifetime, mind you, the lifetime of the product itself (aka forever). Finally, having ensured minimal repeat business, go ahead and launch your company in the middle of The Great Depression. Now, our business acumen developed solely from watching episodes of Shark Tank, but this sounds like an awful idea. Yet, here we are, some 83 years later, and the Zippo brand continues to thrive. Why? Well, there are a number of reasons—a determined founder, some clever ad placements, war—but one that shouldn’t be overlooked is collectibility, which is something Zippo has catered to—both knowingly and unknowingly—since its earliest days.

About 30% of Zippo’s sales are to collectors, according to Patrick Grandy, the company’s Corporate Media and Communications Manager. But that’s a figure that doesn’t happen overnight—hell, it took Ty Inc. seven years before people camped outside of Hallmark stores for Beanie Babies—and Zippo’s story of collectibility really begins in 1939, almost a decade after the company was founded. As World War II began, Zippo ceased producing consumer models of their windproof lighter and focused on supplying the army. With brass being required for military machinery, Zippo produced lighters made of steel instead and coated them with black paint so they wouldn’t corrode on the battlefield. This special wartime model would become known as “Black Crackle” due to the cracking of the paint. It’s the Zippo that started the collectible craze, and it’s a Zippo collector’s holy grail.

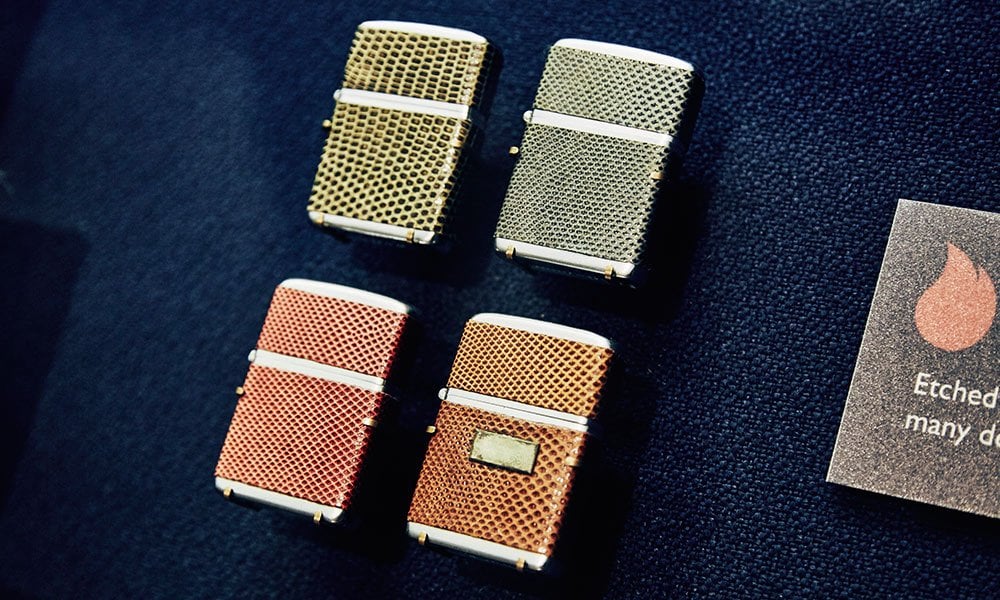

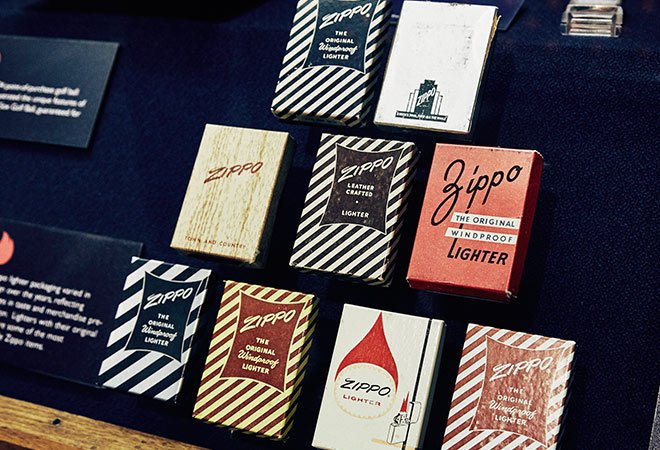

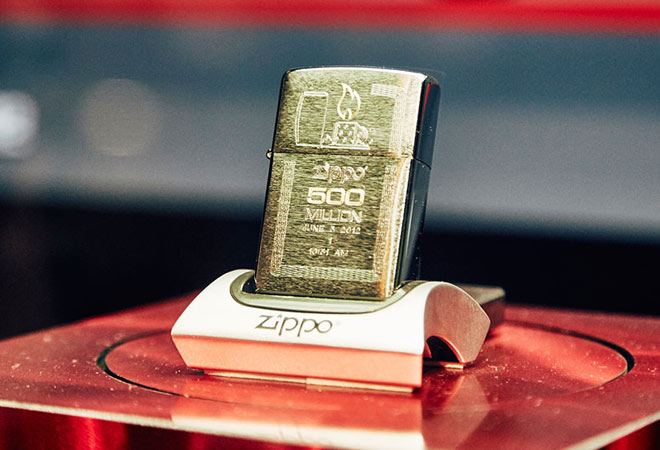

With Black Crackle in mind, Zippo would go on to do other extremely limited editions of their standard pocket lighter, each helping cement a loyal following of collectors. There was a Zippo made for every Mercury and Apollo mission. There was the highly collectible Town & Country series produced between 1949 and 1950. There was the Desert Camo model made for both Operation Desert Storm and Operation Desert Shield. There were leather wrapped versions, plain brass ones, and special models made on the day Zippo crafted its 500 millionth lighter (June 5, 2012). All collectibles.

It wasn’t always Zippo doing this on their own. When a company with some serious money to spend approached Zippo about a custom lighter, Zippo would do more than simply slap the company’s logo on the front of one. Kelvinator received white Zippo lighters that looked like miniature refrigerators. Kennecott Utah Copper received the only Zippo lighters crafted from copper; Alcoa received the only ones made from aluminum. In 1952, GE received Zippo lighters that looked like Ultra-Vision televisions, which some customers received when they bought the TV set. These high-ticket orders produced some of the most desirable lighters the company ever made.

While small-batch models have fostered a collectible environment, they aren’t the only thing Zippo hunters are on the prowl for. What about just old lighters? Well, every Zippo lighter has a date code, a system used internally for quality control, which allows collectors to see when a particular lighter was produced. The code, which is stamped on the bottom of every Zippo, displays the year and the month the lighter was made. While the marks have changed over time, the system makes dating a Zippo very easy. Think you found one from the mid-1900s at the flea market? No need to go on Antiques Roadshow, just flip it over. With the date code in place, collecting old Zippos is as easy as collecting old coins. (You can learn more the dating code here.)

Also stamped on the bottom of every Zippo lighter is the town where it was made—Bradford, PA. Except, not always. You see, there was a period when Zippo operated a factory in Canada (tax purposes), and lighters that came from that factory were stamped with “Niagara Falls, Ontario,” in place of “Bradford, Pennsylvania.” Since Zippo Canada’s production wasn’t close to that of Zippo USA, a Zippo from the land of poutine is a must-have for any serious collector. It’s just another for your checklist.

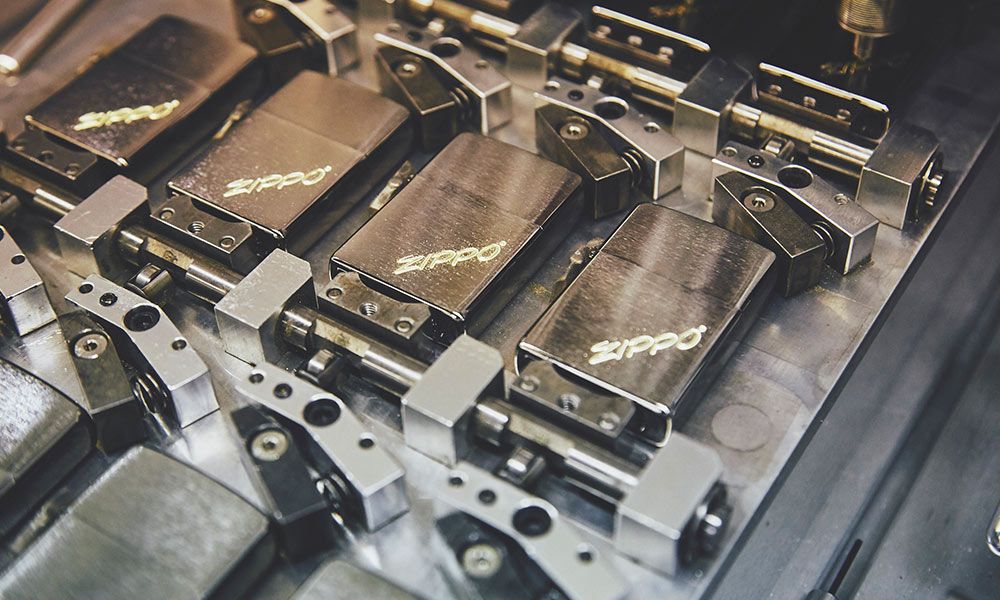

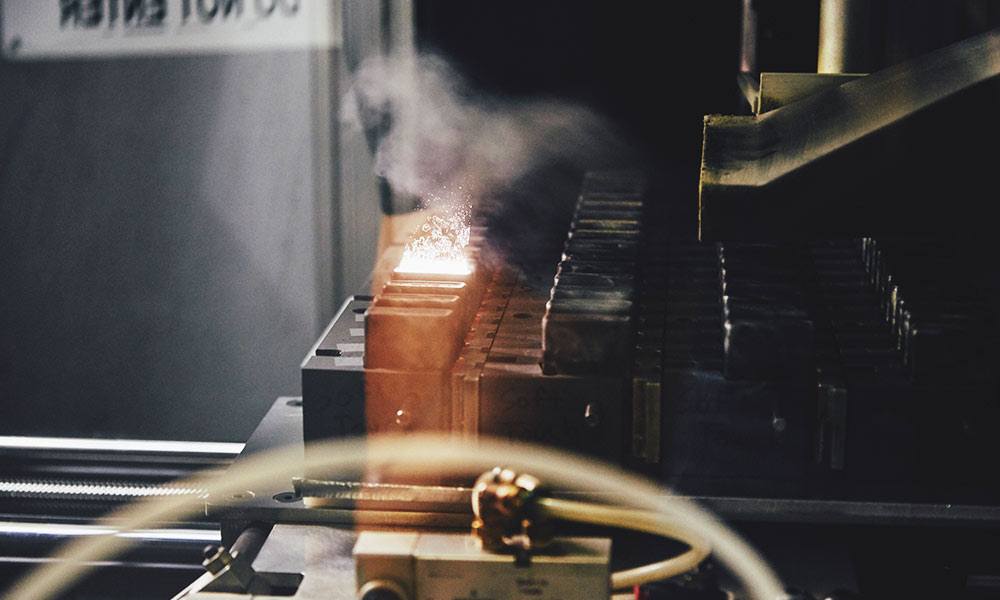

And this trend goes on, with small runs and new designs. Today, Zippo’s design center comes up with 30 new creations every year. Some of these are destined to become collectibles, while the others will sell to their respective audiences. The company even takes one day out of the year to produce a few 18K gold versions, which are hand polished and cost over $10,000 each. Perfect for Bond villains and collectors with cash.

As if the lighters themselves were not enough, it is perhaps the failed experiments that drive collectors the craziest. There was the ZipLight, a flashlight that looked like a regular Zippo lighter. There was a Zippo with a built-in tape measure. There were even table lighters that looked like mini tombstones. All of these came and went. The quicker they did, the more desirable they became. Then there were the ones that never left the factory at all but could have slipped out in the pocket of an employee—a Zippo with two wheels, a combo cigar lighter and hand warmer, and many others. Crazy rarities that could push your collection to museum status.

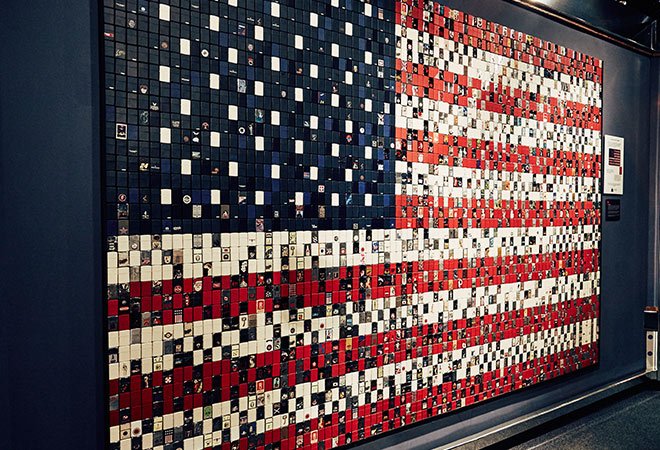

There is one question that remains, however: Couldn’t any company make limited versions of their products, funky mistakes, and rarely seen oddities to gain a following of collectors? Well, they could try, and many do, but what makes Zippo’s model really tick is a certain cool factor birthed from a long history, some clever placement, and a lot of famous fans. John Wayne had custom Zippo lighters with “Stolen from John Wayne” on them because his were always swiped. Don Draper and company lit their Lucky Strikes from Zippo lighters sent to the Mad Men set. Frank Sinatra was buried with one—and unless Bill Murray goes six feet under with a collection of Pogs, that’s gonna be tough to top. When you have a product perfect for collecting—many iterations, a reasonable price tag (minus that 18K gold number), a long history—and you factor in a certain je ne sais quoi, you have something that will spur the creation of collectors clubs (there are many), fan pages, and rabid collectors all hunting for Black Crackles, old date markings, and a two-wheeled Zippo that somehow slipped out of a factory in Bradford, Pennsylvania.