IKEA is one of those companies that it’s impossible to imagine the world without. We can easily picture Frederick Douglass scribbling away at a Lommarp, Emerson reclining at Walden Pond in a Hamnön, and the warrior queen Boudica sticking a few Roman heads on top of a few Tågarp. But as timeless as it may seem, IKEA’s only been with us for just under 80 years. What an interesting 80 years it’s been though.

Not only did IKEA revolutionize the way we think of buying furniture, but it also introduced Swedish design principles to the whole world. We’ve attempted to capture a comprehensive history of IKEA – from its early days as a simple venture in rural Sweden to the forward-thinking international powerhouse it is today.

The Origins of the Swedish Straw Billionaire

The Tale of the Straw Millionaire is a Japanese folk tale about a peasant who trades his way up from a single piece of straw to a massively successful farm. That concept should sound familiar too. There’s a trading minigame in most Legend of Zelda installments, Dwight tries the same thing at a garage sale in The Office, and a very real Canadian turned one red paperclip into a two-story farmhouse. Ingvar Kamprad, the eventual founder of IKEA, is like a child-prodigy version of the straw millionaire. Granted, he didn’t do direct bartering, but each of his business decisions reads like the trading of a man who wants to eventually conquer the world.

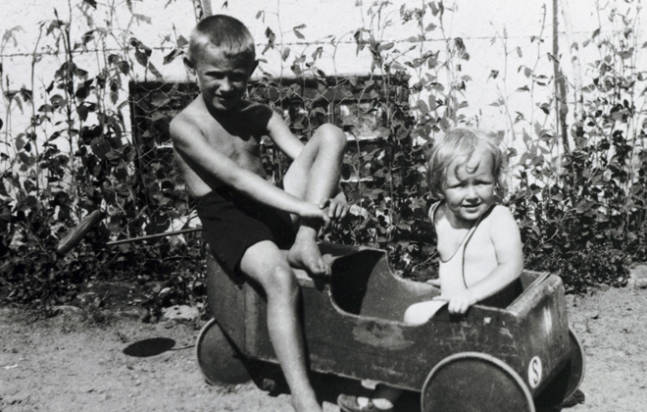

Kamprad’s family owned a small farm called Elmtaryd near Agunnaryd in Småland, Sweden, an area that famously produces more stone than crop. People in the region are famously financially creative. Especially around the time Kamprad was born, in 1926, most Smålanders had some kind of side business going. For Kamprad’s part, he started selling matches in 1931 when he was five. His grandmother was his first customer, as is the case with so many homegrown businesses. The business itself was simple. His aunt bought matches wholesale in Stockholm, then Kamprad repacked them smaller and sold them for a small profit, which he saved and reinvested into his own expansion.

By the time he was 13, he’d moved from matches to a bicycle-powered farm-to-farm service that sold fish, seeds, Christmas cards, and magazines. In true Kamprad fashion, he started with his mother’s bicycle until he’d profited enough to invest in a bike of his own. At the same time, he was running the bike-shop-and-delivery service, he talked his father into buying larger nets for the family fishing boat, which allowed him to sell more fish and put aside even more money for future investment.

Moving to boarding school at 14 presented a challenge. Obviously, Kamprad couldn’t keep delivering to neighboring farms. At the same time, he wouldn’t let himself just stop selling stuff. He pivoted to watches, pens, wallets, and belts, all things that would appeal to his classmates. At some point in his three years at boarding school, Kamprad set his sights on owning and operating his own firm, where he’d basically formalize the business he was already doing. This also made his father’s graduation gift a no-brainer. Mr. Kamprad paid IKEA’s registration fees in 1943.

Let’s also take the mystique away from the meaning of the name. The name IKEA is basically an address: Ingvar Kamprad (his name), Elmtaryd (the family farm he grew up on), Agunnaryd (the closest town to the farm).

The Rise of IKEA, a Scandinavian Startup

The first few years of IKEA looked pretty much like an expanded version of what Kamprad had already been doing. It was a mail-order service based in Älmhult, the same town where Kamprad’s grandfather ran a general store and where the modern IKEA design headquarters are found. The first brochures offered household goods – watches, picture frames, pens, jewelry, and stockings – for low prices, dealing mostly with the rural areas Kamprad was more familiar with. Deliveries were made out of the back of a milk van Kamprad hired.

Furniture wasn’t offered for the first few years. Even in 1948, the first year he included any in the brochure, Kamprad deferred to customers to dictate how the company should proceed. If there was interest, he’d stock more. If there wasn’t, he’d go back to what people were actually buying. As it turned out, they wanted to buy furniture. They wanted to buy so much furniture it was the main offering of the first catalog in 1951.

Not that IKEA’s first furniture offerings were met with equal support. While anyone who actually bought furniture was happy with the product, there were many more who couldn’t believe that furniture could come at such a low price. This idea was so pervasive that Kamprad had to open a showroom in Ämult in 1953 so people could touch the furniture for themselves. The showroom model proved effective, so IKEA opened its first store in 1958, also in Älmhult.

The Story Behind IKEA Furniture

Furniture was also a unique challenge and opportunity for IKEA. When they first started, their pieces, and furniture in general, came as solid pieces. It was bulky, heavy, and the exact opposite of efficient. Which is the exact problem draftsman Gillis Lundgren solved in his early years at IKEA.

A table Lundgren was shipping (or had bought for himself, sources aren’t exactly clear) wouldn’t fit in his car trunk. He decided to simply unscrew (or saw, again the sources aren’t super clear) the legs off the table. Since IKEA is such a fan of simple, efficient solutions, it was fairly easy for Lundgren to move the company to a flatpack format. The first product the method was used for was the Lövet in 1956, a table you can still buy under the new name, Lövbacken.

It should also be said that IKEA achieved all of this in the face of stiff, often underhanded competition from other Swedish companies throughout the 1950s. These other companies would use whatever power they had to undermine IKEA’s rise, including pressuring other suppliers to cut ties with IKEA. Some did, which is where IKEA’s collaboration with foreign suppliers and manufacturers started.

The 1960s were a time of localized expansion, both in the stores themselves and in IKEA locations in other countries. IKEA expanded into dining in 1960 when Kamprad noticed customers would leave the Älmhult location empty-handed if they were hungry. He figured, correctly, they would make more sales if customers had meal options in the store. In 1963, IKEA opened an Oslo location, the first store outside of Sweden. In 1965, Kungens Kurva, the flagship store outside Stockholm, opened, looking like the IKEA version of the Guggenheim. Sundsvall and Malmö, both in Sweden, got their own storefronts in 1969.

1970 proved to be another pivotal year. The flagship store that we were just talking about, Kungens Kurva, just about burned to the ground (there were no human casualties) thanks to an electrical fault in the neon sign on its roof. It was a bit of fiery salvation though. Up until the fire, Kungens Kurva had been experiencing massive wait times, overcrowding, and delivery issues.

The fire forced them to rebuild but allowed them to reconceptualize how they operated their stores. The biggest change was allowing customers into the warehouse for the first time, streamlining the selection, delivery, and checkout process. The fire of 1970 created the IKEA modern customers would recognize.

IKEA’s Growth: Furniture Vikings Invade Europe, then the Rest of the World

IKEA stayed in Scandinavia up until 1973, when store openings started to gain momentum. 1973 saw a new location in Zürich, 1974 saw Munich, then 1975 to 1979 had 19 store openings in places all over the world, including Sydney, Hong Kong, Vancouver, Vienna, Toronto, Edmonton, and Berlin. This brought their total location count up to 29, which is impressive on its own, but pales in comparison to the openings of the 1980s. Which, in turn, pales to the 90s, which pales to the 2000s. You can see the pattern here. IKEA keeps opening stores, and we could spend the rest of this article in awe of how far flung some of these places are. We won’t hit every single one, but let’s at least list some notables.

First, here’s some local pride. The first IKEA to open in the United States was in Philly in 1985. Thankfully, the Swedes didn’t go the way of the hitchhiking robot.

The largest IKEA, as of this writing, is in the Philippines, in the city of Pasay in the Mall of Asia and measures a mind-boggling 730,000 square feet. The store size isn’t actually much bigger than a normal IKEA though. They’re folding a couple different operations into the store, inflating its size.

There’s an IKEA museum in Ämhult. They were an invaluable resource in writing this article and their exhibits do an exhaustive job laying out the history of IKEA. Plus, the museum shop carries exclusive IKEA products, which could end up meaning you buy something worth using from a gift shop for once.

We didn’t know until we started researching this article, but the IKEA Hotell has been operating in Ämhult since 1964. It’s the perfect encapsulation of IKEA’s core principles. It’s furnished with IKEA products, serves Swedish food, and emphasizes the Swedish Lagom style. We’d call that last thing minimalism, but that’s not quite accurate. It’s more about providing exactly as much as you need without indulging in luxury or languishing in deprivation.

In a rare move, IKEA’s shown that it’s not opposed to strategically shrinking its market share either. After Russia invaded Ukraine earlier this year, IKEA closed all 17 of its Russian locations. So far, they’ve left their Mega brand shopping centers open so as not to cut the Russian public off from their daily needs. To which we say, yeah, that’s probably a good idea. There’s a big difference between stopping the public’s access to new chairs and stopping their access to food.

A Sustainable Future for IKEA

Part of IKEA’s ongoing success is thanks to their unique corporate structure. The IKEA that we interact with is actually owned by INGKA Holding B.V., which is owned by Stichting INGKA Foundation. Normally, we’d be suspicious of a company with different subsidiaries and holding groups, but IKEA’s structure is reassuring for one major reason. The corporate structure is set up so profits from IKEA can be either reinvested in IKEA or used in the charitable arm of the Stichting INGKA Foundation. Put even simpler, IKEA can either improve IKEA or the world.

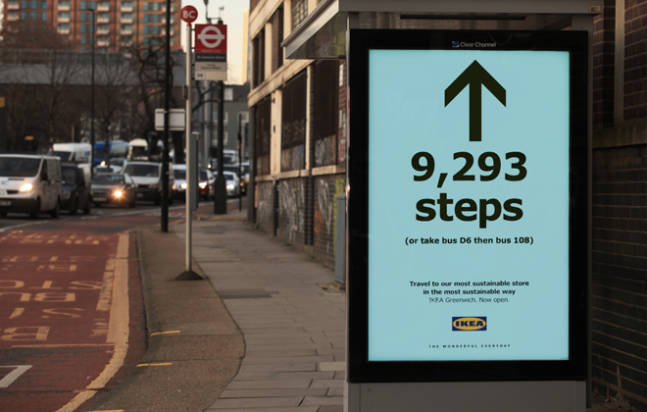

This overachievement extends to their larger operations as well. IKEA’s pledged to be climate positive by 2030. To run through a few of the customer-facing improvements, IKEA is redesigning products to be more energy-efficient, lending cargo bikes so people don’t have to drive to their stores, testing furniture rental programs, providing charging ports for electric vehicles, and researching how to make their wood products’ life cycles circular. That last one means they’d be reclaiming the wood from products customers would have otherwise thrown away, which would have put the carbon back into the atmosphere. This is in addition to the astounding amount of sustainably produced wood they already source from their FSC regulation-compliant woodlands.

In a much larger offering, IKEA is currently selling solar panels in 11 markets (which sadly doesn’t yet include the US) and they’ve started selling renewable energy in the Swedish home market. If the past is anything to go by, success there means it’s only a matter of time before the rest of us can buy IKEA-produced energy.

Most recently, IKEA’s carbon emissions fell 6 percent from pre-pandemic figures. It’s a considerable drop for a period that includes increased sales and bodes well for the future of their climate positivity pledge. It’s also a welcome bit of good news in an otherwise bleak landscape. If a company as big and complex as IKEA can make changes that are so at odds with their existing structure, maybe we won’t all die in the climate’s manifestation of mankind’s hubris. Maybe the future of mankind is living in sustainably built, Swedish-designed minimalist flat-pack homes powered by the sun, sitting in pinewood chairs, eating lingonberry jam, and cramming weird vowels into off-kilter words.